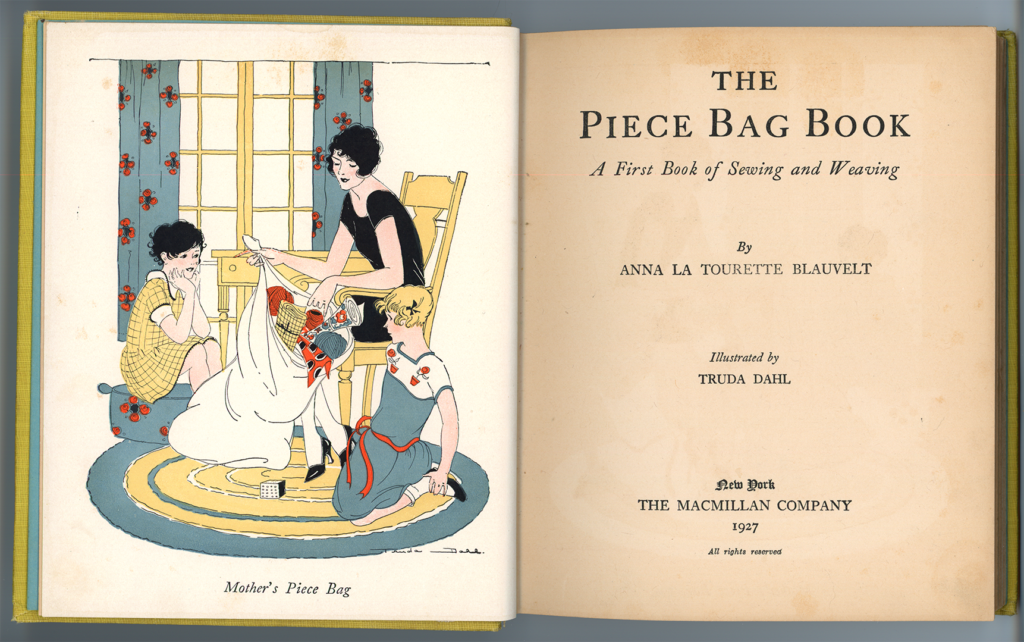

Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 9 Oct 1891

There were actually two men of the cloth, both from England, both who preached in Tivoli between 1891 and 1903, and both who caused an unbecoming scene during services at their respective churches that made the newspaper. The latter, Rev. Evan Valentine Evans, was part of Historic Red Hook’s Cemetery Crawl, so I won’t repeat myself. Find that sad story at Historic Red Hook. The former you’ll learn about here. If I find a third I’m going to have to go for a PhD on the subject.

Rev. Evans’ story is tragic and even sympathetic, but Rev. John H. Boyes’ tale is that of a complicated man in a high-profile occupation who repeatedly made a bad situation worse. Let’s get introduced to Boyes, then go back along his timeline to see how his life went off the rails.

First, it’s important to mention who Rev. J.H. Boyes was not. His name was spelled “Boyes,” and was misspelled every way possible in newspapers, especially in our area where Boice or Boyce is a common surname. He was not farmer John H. Boyce, born c.1855, who resided in Wayne Co., NY. He was not Rev. J.H. Boyce (first name Jacob), a Methodist who served over 60 years, at one point in Wayne County and other locations in New York State but mostly in Pennsylvania. He was also not Rev. J.H. Boyce of New York State, a Methodist missionary active into the 1940s.

[If you want to see each source appropriately footnoted, please click HERE for a pdf version of this article. I can’t figure out how to footnote in WordPress!]

John H. Boyes was born c.1850 in England. He began his work as a clergyman around 1880 (coincidentally the year that the Tivoli Baptist Church constructed the building in which he would later preach). Three years later on May 16th, 1883, Boyes married a Canadian woman named Lucinda Staples in Wellington, Ontario, Canada, then came to the US in 1884. John and Lucinda had eight children, only four of whom lived to adulthood and who were born in New York State, Violet 1884, Grace 1886, Benjamin 1887, and John 1889. He worked as a Baptist pastor in Williamson, Wayne Co., NY, Himrod, Yates Co., NY, Atlantic Highlands, Monmouth Co., NJ, and Tivoli, Dutchess Co., NY.

In the 1900 census taken in Manhattan John H. Boyes’ occupation was listed as “artist” and, indeed, the Poughkeepsie News-Press said that he had “earned a promising reputation as a portrait painter. His work has found its way into some of the best and most cultured homes of Poughkeepsie.” The reporter also thought “it really looks as if painting is the best way out of any church trouble that Mr. Boice [sic] may have had.” He also worked in crayon (the art type, not the Crayola type), exhibiting and winning prizes for his portraits in the Yates County Fair.

The “Church Trouble”

Boyes was a Baptist pastor by profession who considered himself an artist at heart. He seemed to be a dyed-in-the wool Baptist and dedicated to his task. The Red Bank, NJ Register reported that he was “a good preacher, and an earnest worker, and his labors in the churches of which he has formerly been pastor have been markedly successful.” While working in New Jersey he added services and made Sunday school meet earlier in the day. While in Williamson, he invited speakers to come to his church to talk about temperance, and he held public meetings to argue that “the teachings of the New Testament are superior and more conducive to human happiness than the teachings of Secularism.” It would seem he was a man who believed he knew How Things Should Be, but perhaps to the detriment of being gainfully employed. Only a short time into his tenure in New Jersey he argued that he was more forward-thinking than his employers, the trustees of the church he served, who had, in his words, “narrow, contracted ideas” as to how to minister to the congregation.

Boyes must have seemed good on paper to be hired by four different houses of worship. He received praise and exhibited dedication and a desire to go above and beyond what was expected of him. But like so many who make their fortune through something other than that which gives them the satisfaction their hobbies do, it would seem that Rev. Mr. Boyes was often more concerned with getting paid than doing right by his flock. He spent just under two years in the employ of each congregation that hired him.

Early Career

Rev. Boyes’ first (or perhaps second) stateside gig was in Williamson, Wayne Co., NY, east of Rochester. When he attended a Baptist convention in Rome, NY in October of 1884 the newspaper said that he hailed from “La Fargeville” (north of Watertown and 125 miles from Williamson) but I could not find a record of his employment before Williamson. As a married Baptist pastor in his thirties with small children, he seemed poised to make a nice life for himself in America. However, just two years later his reputation would be announced far and wide by syndicated news when in July of 1886 he sued Baptist Weekly magazine for $50,000 for libel.

The magazine printed “[Baptist] Churches are warned against receiving Rev. J.H. Boyes as a minister. He has a bad record” in their July 1st, 1886 issue. In the following pages, you will learn why they may have felt it important to state this for the record. Shortly after the July issue was printed, the Palmyra Democrat reported about the suit, saying that Boyes “…has always borne an excellent reputation and has certificates of commendation from every society to whom he has preached. He is an original thinker and an able speaker…” which sounds not unlike words he would say about himself. As this was his local paper and the syndicated story wouldn’t be picked up for another two months, the possibility that Boyes wrote and submitted this story himself is fairly high. The case was to come before the circuit court in November in Lyons, but, before that could happen, the magazine printed a retraction “saying that the reflections on the reverend gentleman were caused by a correspondent who had been misled” and the suit was undoubtedly dropped as there is no more mention of it after 1886.

Rochester Democrat and Chronicle 21 Aug 1886

The first notice advising congregations against hiring Boyes was printed in July. Despite the story being picked up by numerous papers, his next three employers appear to have been none the wiser. By September he left Williamson and was hired by a church in Himrod, Yates Co., NY where he worked for a year and a half. In February 1888 in Himrod, he and Lucinda added a baby daughter, Olive to their family. Boyes was briefly absent from work in April 1888, the same month in which the Red Bank, NJ Register reported that he had been hired to preach at Atlantic Highlands Baptist Church., His departure from Himrod seems to have been a smooth one, at least as far as was reported. He preached a farewell sermon in late April, was on his way to New Jersey the following week, and began his pastorate there in May of 1888. In August, he and daughter Olive were ill with a “brain fever” (possibly scarlet fever). John recovered, but Olive died on August 14th, one of four children the Boyes family would lose before 1900.

Trouble in New Jersey

Nine months after beginning work in New Jersey, at a business meeting of which Boyes (as their pastor) was the chairman, the trustees of Atlantic Highlands (all of whom had the surname Leonard) asked him to resign. They felt his “ministrations (had) not been satisfactory to a part of the membership.” They had him relinquish the chair to another board member so that the board could discuss his departure. When he returned, Boyes said he wanted some more time to think about it, but waffled saying he may or may not resign. They got him to leave the meeting again and resolved to get him to resign by May 1st, 1889 or “the church members would take matters into their own hands.” When he couldn’t be located to return to the meeting, they simply voted to fire him.

That Sunday, during morning service before his sermon, Boyes used the pulpit to complain about this development in his career to those in attendance. His sermon talked about “prophets who prophesied smooth things” thinly veiling “ those who had led him to believe that everything would go smoothly” when he took the job at Atlantic Highlands. The Sunday evening service was reported to be more personal than the morning, resulting in the members becoming even more convinced they needed to get rid of him.

What exactly was it that irked the members and deacons so much about Boyes that they felt they had to not only ask him to politely resign, but to insist when he didn’t immediately agree to do so? Unfortunately, the only statements found alluded to the members being unhappy with the way he preached—that “his services were unacceptable to the church.” If you are so bad at your job that your employer fires you, do you hang around, dig your heels in, and say ‘no, boss. I’m awesome and you’re dumb and wrong’? Truly baffling behavior.

The trustees of the church at first fired him effective April 15th, he countered with June 1st, then they compromised with paying him through May 1st, but with the understanding that he was done preaching effective April 15th. They wanted him out of the pulpit that badly. Boyes refused.

The Atlantic Highlands trustees must have had some serious concerns about his conduct or fear over what kind of a scene he would make, because at a business meeting on April 19th they resolved to close the church building for cleaning from Sunday until further notice. They claimed they wanted to get the cleaning done by May 1st, which just so happened to be the last day they would pay Boyes. They did this, despite the fact that the first Sunday of the two-week period the Atlantic Highlands Baptist church would be closed happened to be April 21st, 1889—Easter Sunday.

Red Bank Register 24 Apr 1889

Boyes read about this closure in the newspaper and declared that he would hold service even if only two people showed up to hear him, so the church got police to patrol the premises to keep him out. When he rolled up Sunday morning, there were four congregants present outside the building and when the police directed Boyes’ attention to the closure notice, he politely left, pointedly displaying a calm and gentlemanly manner. The Red Bank Register ran two long articles about the drama, titled “THE PASTOR MUST GO” and “THE PASTOR SHUT OUT”, and it seems that the trustees won. Aided perhaps by the fact that Boyes had another job lined up and would leave the state in short order, the drama seems to have ended there. For them.

Tivoli

At their regular board meeting on April 9th, 1889, the trustees of the Tivoli Baptist church voted to hire Rev. John H. Boyes for $700 a year (with donations) through May 1st, 1890. After the move to New York State, a son, John, was added to the Boyes family in August of 1889.

Only eleven months after beginning work in Tivoli things weren’t looking good for the problematic pastor. Trustee Philip Peelor asked Boyes to resign so that a previous pastor, his son-in-law, Rev. Ferris, could return. Boyes refused, but it turns out Ferris didn’t even want the job. He had had “considerable trouble” during his pastorate of the Baptist church because he was a young widower and the unmarried women in the congregation fought over him. Boyes was also in some financial trouble with the Peelors, owners of a dry goods store in town, owing them over $170 for past due bills. They cut off his credit to their store when he didn’t pay his debt. It’s fair to say the Peelors were not fans.

When Boyes’ contract with the Tivoli Baptist church came up in 1890, a clause was added; if either Boyes or the trustees wanted to end his employment mid-year, either party could do so with 30 days notice. In another parallel with the New Jersey job, by the spring of 1891, a simmering “dissatisfaction” had been brewing amongst the trustees and members with how Boyes led the flock. One of the trustees stated that “at frequent periods it was suggested to the pastor, that for the good of all concerned, both himself and church, that he resign.” Boyes would claim that Peelor threatened him somehow when he demanded his resignation. According to some accounts, Boyes wrote up a resignation letter himself and showed it to some of the members, saying he would bring it to the trustees but never went through with it. Whether this was just unhinged behavior or a sympathy tactic remains unclear.

Per the new contract that allowed them to give 30 days notice, at their business meeting in February, the trustees resolved to terminate Boyes effective May 1st, 1891.

No, you are not mistaken. This is the same thing that happened in New Jersey. But before you get bored and stop reading, wait for it. If you think he was problematic in 1889, Boyes is about to tell you to hold his beer. Unlike the situation at Atlantic Highlands where they battened the hatches and held firm until the storm that was John H. Boyes had passed—the trustees of the Tivoli Baptist church were not so lucky or level-headed in their dealings with this difficult and manipulative man.

In another situation eerily similar to that of Atlantic Highlands, at this pivotal late winter business meeting, the trustees of the Tivoli Baptist church asked Boyes to vacate the chair so they could pass the resolution to fire him. Boyes claimed he closed the meeting “on the ground of disorder, and that it was an illegal meeting.” He said his enemies ganged up on him and that people who didn’t usually attend these business meetings were in attendance. The trustees claimed that he gave up the chair when asked to do so and another trustee, P.N. Martin, was made chair temporarily to pass the measure 16 for and 4 against being done with their pastor. When they asked Boyes to retake the chair and wrap it up, he refused to do so. Martin then retook the chair and officially closed the meeting.

To make it official, they served Boyes notice of the resolution through the mail. Knowing what we know of his previous actions, one can imagine they felt it necessary that their Is were dotted and Ts were crossed. This was a good thought, but they made a crucial mistake that the folks at Atlantic Highlands had avoided—they didn’t physically keep him away.

During the Sunday evening service following this business meeting, depending on whose story you believe, either Rev. John H. Boyes read the notice he’d gotten in the mail, or he refused to do so and a trustee read it to his congregation, but either way, Boyes declared that he would not accept it and “made a lot of sarcastic remarks from the pulpit about the Peelors and others.” One trustee noted that the church had been debt free before Boyes arrived and was now $800 in debt. No further details are given, but perhaps he asked for loans, or the donations that would pay for his salary had understandably dried up. If there was an inkling of his misappropriating funds, it surely would have been reported. At a subsequent trustees meeting at which Boyes (still the acting pastor) was in attendance “there was some lively talk between [Boyes] and the trustees and a constable was called in.” Just bringing a cop to the meeting must have cooled their jets enough that a further scene did not develop.

As May 1st, 1891 approached, the trustees became nervous because it sounded as if Boyes really was not going to take ‘you’re fired’ for an answer. They consulted with lawyer Fred Ackerman from Poughkeepsie as to what they could do, and he suggested they put a police officer next to the pulpit “and tell Boyse [sic] not to go in the pulpit, and if he resisted to arrest him at once and take him before a justice.” They also secured a previous pastor of their church, Rev. Joshua Wood who served in the 1870s, to fill the position starting with Sunday services on May 3rd.

Owing to Boyes’ odd refusal to accept his termination, it made sense for the church to be so nervous as to what this man might do and to make preparations, however, Boyes was making preparations of his own.

May 3rd, 1891, Tivoli, NY

Boyes attended the morning service on May 3rd, conducted by Rev. Wood at the Tivoli Baptist church and all seemed at peace, but that would change by Sunday night.

Red Hook Journal 8 May 1891

A crowd of hundreds of Baptists and onlookers packed the church. The trustees also had an officer of the law named Feroe in attendance, as advised by their lawyer. According to one trustee, Boyes brought “all the roughs in the place” with him that night, asking one local in particular, Homer Rockefeller, to “come to the church and see the circus” though Boyes later denied under oath that he said this. He did, however, ask Tivoli constable Zachariah Minkler to come along to “protect” him.

Shenanigans began promptly at 7:30 P.M. as trustee Peter N. Martin witnessed Boyes trying to keep Rev. Wood from entering the church. He “pressed Wood against the door jamb and tried to pull Wood’s hand off the doorknob, so as to get in ahead of him, but Wood got in ahead and started on a little run sort of ‘go as you please’.” Perhaps this was a sort of awkward jog to get away from Boyes and his odd behavior. Before opening services Wood climbed the steps to the pulpit and seated himself next to it. Trustee Sylvester Teator, seated nearby, watched Boyes come in and attempt to make small talk about the weather with Martin who asked Boyes to be seated. Boyes sort of half-sat, half-stood in the first pew, with one foot on the seat, looking back at the doors for some sign to go into action. Perhaps he was waiting for the doors to close or for certain witnesses to either be present or not be present yet. It’s unclear what the trigger caused him to leap over the pew and rush the pulpit where he “plumped himself down right along side of brother Wood.”

Boyes then stood up at the pulpit before Wood had a chance to take his place, picked up a hymnal, announced Hymn No. 61 and started to sing. Someone in one of the court hearings that would later arise from this event claimed this was “Nearer my God to Thee,” but, perhaps unsurprisingly, the organ player and those gathered simply watched in stunned silence while Boyes sang a verse by himself.

Rev. Wood then got up, and, rather than confront Boyes, tried to read some scriptures as if nothing were amiss, prompting a “lot of young fellows” at the back of the church to laugh at the ridiculousness of it. Undeterred by this awkwardness, Boyes picked up a Bible and started to read from it. It was then that the trustees began to respond. Martin asked trustee Robert Worthington to get a police officer to arrest Boyes, but Worthington, 100% done with these antics, unwittingly played directly into his hands.

Worthington tried to wrest the Bible away from Boyes, aided by Rev. Wood and they did a bit of a tug of war with the Good Book in front of the astounded congregational audience. Worthington yelled “I’ll take him out of there!”, grabbed Boyes, and pulled him out of the pulpit as the hundreds of parishioners seated in the pews freaked out.

Zachariah Minkler said that when he came into the Baptist church, the first thing he saw was this altercation as the former pastor was dragged down the steps from the pulpit by Worthington who called for the service to be closed as the struggle went on. Boyes would report that Martin also had hands on him and that he was thrown to the floor, “his buttons torn from his clothes, and suspenders torn loose” but no other report (not even the more sensational recollections of Minkler) mentioned this. The trustees asked officer Feroe to arrest Boyes, but Feroe said he didn’t think he had the right to do so. Worthington then asked Minkler but he wouldn’t do it without a warrant.

Minkler would later state that some folks in the crowd who had not yet fled the building rushed toward the pulpit to break up the fight, and that Worthington shouted “Any man who touches me I’ll sock him through the wall!” Minkler ordered Worthington to lay off Boyes and grabbed him, asking Feroe to help him prevent a riot.

“…the church was thrown into an uproar. Ladies fainted, children screamed and pandemonium reigned…” Minkler then asked Boyes if he thought it was his congregation to control and if so to close services properly. As Boyes got up and attempted to pronounce the benediction, taking up the hymnal again to announce hymn No. 26, someone (according to Boyes) shouted “You can’t sing here; let’s have a riot!” He noted that Worthington especially shouted him down yelling “You can’t pray here!” and “Bah! Bah! Bah!” When Boyes said “we will close with the benediction” Worthington said “No, you won’t!”, ascended the pulpit steps again, and physically tried to stop Boyes from talking. Somehow, in this effort, Worthington’s fingers ended up in Boyes’ mouth. This would be interpreted by the embellisher Minkler thusly:

“…Worthington ascended to the platform and slapped the dominie across the mouth two or three times with the back of his hand, but the dominie finally got through with the benediction, Worthington saying to him, ‘You ain’t half a man.’” Three men, Fred Ross, Charles Moore and Officer Minkler, had to restrain Worthington.

Having achieved the chaos he sought, Boyes left the church and Rev. Wood either continued the service for those who remained or simply closed it.

Post Card of Broadway, Tivoli showing fire house (library etc. now) and Baptist Church which became the Legion hall before it burned in the 1990s.

When one leans back and observes these actions from the comfort of hindsight, it’s remarkable to see how this scenario played out twice (once unsuccessfully in New Jersey). They are so similar it’s hard to believe Boyes did not plan them. When he didn’t get to lead the flock the way he wanted, he was terminated, then enacted a histrionic tantrum in order to rake the board of trustees over the coals on his way out.

After the scene in Tivoli on the evening of Sunday the 3rd of May, Boyes “…left the church followed by nearly the whole congregation, whose sympathies were entirely enlisted in his favor. Boyse [sic] did not offer the slightest resistance, but submitted to the indignity heaped upon him by Worthington without complaint or murmur.”

Saint John, the unfireable.

He had set up a sensational, public display of aggression against him by his employers. The mean old church trustees were painted as the bad guys who pushed a good, well-mannered, pious man out of a job. Initially, it seemed to have worked. Members of the dePeyster and Livingston families attended court hearings held in Tivoli and those friendly to him raised $100 to offset legal costs. But the author of the article in the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle of May 6th, 1891 said it best (without having any knowledge about the Atlantic Highlands incident): “There was no need of any such proceedings as occurred there last Sunday night. …the church should have been locked up until the matter was legally disposed of. That would have saved the town a disgrace that will take it a long time to get over.”

The next part of Boyes’ plan (if it can be called such) would unfold in the coming days and months, but ultimately, because it was insane to begin with, it would fail.

A hearing was held in Poughkeepsie in which Boyes accused the trustees of preventing him from preaching in the church and thus interfering with the freedom of religion. They were tasked with showing cause for blocking him because Boyes was hoping to get paid a salary owed to him, believing that he was contracted to be employed by the Tivoli Baptist church for another year. A week or so later an anonymous trustee wrote in to the Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle to clear the air. He stated for the record the dates when the meetings were held, when Boyes’ contract was renewed, and that a clause was added for a 30-day notice of dismissal. This information was also entered into the record at the hearings that would follow the May 3rd incident. But Boyes wasn’t quite done yet.

On the evening of Monday, May 18th, 1891 the trustees gathered at 8 P.M. for their monthly meeting at which they would elect officers for the coming year. They were shocked to find Boyes approach and declare that because (he believed) he was the active pastor, he should continue to chair the meeting. Robert Worthington, who had been the one to manhandle Boyes on the 3rd, snapped. He threw Boyes to the floor and wailed on him, either shouting “I will kill you!” or simply cursing him out, then picked him up and tossed him out of the church and down the front steps. Given Boyes’ previous actions, what he did next is not as surprising as it might seem. He got up, and attempted to enter the church again, but Worthington and others prevented him from doing so. A crowd outside the church had their eye on Worthington and were apparently ready to beat him up, but the trustees pulled him back in and closed the doors. Boyes later went to the police and they issued a warrant for Worthington’s arrest on assault charges.

Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle 20 May 1891

A trial was held in Tivoli before Justice Champlin on June 2nd, this one, in a surprise twist, was against Rev. John H. Boyes for disturbing a religious meeting. Prosecutor George Esselstyn represented the trustees and William H. Wood stood for the defendant. William Wood argued that “the facts stated in the complaint were not sufficient to constitute a crime or a misdemeanor under the statute,” that Boyes didn’t make any disturbing “noises” and that he was “compelled” to vault over the pew and take the pulpit by his sense of duty. Wood wanted a jury trial, but Esselstyne argued that holding Boyse until then could “run great risks in a case for false imprisonment.” Justice Champlin, after statements from the trustees were heard, declared “that the complaint has been proven clearly against the defendant, and the court holds him to await the action of the grand jury, and releases him on his own recognizance.”

“This man won’t run away,” Esselstyn reassured those present.

Someone in the peanut gallery piped, “If he does, it will be all right. We hope he will and hope he will never come back.”

“Don’t be alarmed,” someone else countered. “He’s here to stay.”

Bless the peapickin heart of the anonymous Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle reporter who jotted those lines of dialogue down. Boyes was ordered to appear before the grand jury the following week.

In the meantime, Boyes wrote a letter to the church, only some of which was printed in the Columbia Republican of June 25th, wherein he declared that his pastoral work (that he was fired from, remember?) and his freedom of speech was interfered with and his “personal liberty” was threatened. Attempting to salvage his now failing plan, he informed them that he was scared he’d be hurt again if he tried to do his (non-existent) job, and that he wouldn’t attempt to do so again until they (his former employers) reassured him he would be safe. He held all the members of the church responsible for paying his yearly salary (nope), monthly. He also called out the members for being bad Christians. This doesn’t sound delusional, this sounds like someone who has committed to a bit, despite the whole show having gone severely off the rails. Doubling down on his doubling down would only make matters so much worse for him.

The church and Boyes must have had a meeting or communications after this that resulted in both parties deciding to “let the whole matter drop” as “a trial would be unfortunate to both church and people.” Unfortunately, no one informed the court, so when the case came up and this agreement was announced, the Justice must have shaken his head when he said “it would have saved considerable running around” had he known beforehand. Before they left this session, Boyes wanted it made clear that he did not make any concessions in order to reach this agreement and he still wanted his money.

He continued to preach in Tivoli at least once or twice in the fall of that year at a chapel belonging to Johnston Livingston (the one built c. 1856). Boyes spoke and took up collection to support himself, presumably his family (who are never mentioned in the newspaper reports of the incident or legal proceedings after it), and his legal fees.

An article that appeared in the Columbia Republican that reported this activity, and sounds as if it were written by either himself or his supporters, was conveniently published on the day of the hearing of Boyes’ assault suit against Robert Worthington for $5,000 in damages. On October 8th, 1891, after hearing testimony, Justice Barnard “abruptly” (and understandably) dismissed this case.

“There is nothing here for a jury. I think the [trustees’] meeting in February had a right to discharge this man. There should not have been such an unseemly scene in the pulpit….He ought to have gone. He had no right to force his way into the pulpit. He ought to have listened to his discharge.”

In response, the lawyers “moved for a non-suit” (understandable given the sentiment quoted above—but hard to imagine two instances of physical violence witnessed by hundreds of people summarily dismissed in the 21st century) bringing an end to the nightmare for the Tivoli Baptist church and the beginning of the downfall of John H. Boyes.

If Boyes’ supporters did raise money for him, it wasn’t enough to keep him from defaulting on his debts. In December he was ordered to pay court costs incurred during his attempt to sue Worthington. He could not pay them at that time but said he would be willing to be placed “on limits,” which was sometimes allowed in the 18th and 19th centuries in America. A debtor could be allowed to be at large within geographical “limits” or boundaries encompassing territory around the jail itself. By February, Dutchess County arrested him for failure to pay $375.50 (which would be over $10,000 today). He may have spent some time in jail, because, in April, the request to be allowed to roam within jail limits was denied.

Also in February, the Baptist Church’s former clerk, Charles E. Cole was asked to turn over the books to the trustees, but Cole refused, saying he was elected on March 25th and was permitted to hold the books for a full year. This must have seemed sketchy because Worthington sued Cole to force him to return the books and he was compelled to do so in early March to the new clerk, W.N. Otis. This appears to be the last of the publicity in the local papers over the May 3rd, 1891 incident, as well as the last time Boyes is noted as a reverend, Baptist or otherwise.

John H. Boyes and his family appear in the 1892 census in Red Hook which was enumerated in February of that year, but it’s unknown how long they remained there. Early that year he was painting portraits and his works appeared in the “best and most cultured homes of Poughkeepsie” In 1894 the papers reported that he painted an oil portrait (presumably from a photograph) of Minnie Katherine Cox, the late wife of Frank B. Van Dyne of Cannon Street, Poughkeepsie who had died the year before. He also painted then Under Sheriff (later Chamberlain) Courtland S. Howland of Catherine Street. Sometime between late 1894 and 1900, Boyes moved his family to Manhattan where the census taker recorded his occupation as “artist”. He was also listed as “alien” meaning he had not yet become a US citizen. It’s not known if his career as a portrait painter ever took off. He died at age 50 on January 13th, 1901 and his wife Lucinda Staples Boyes followed three years later on June 23rd, 1904.

Conclusion

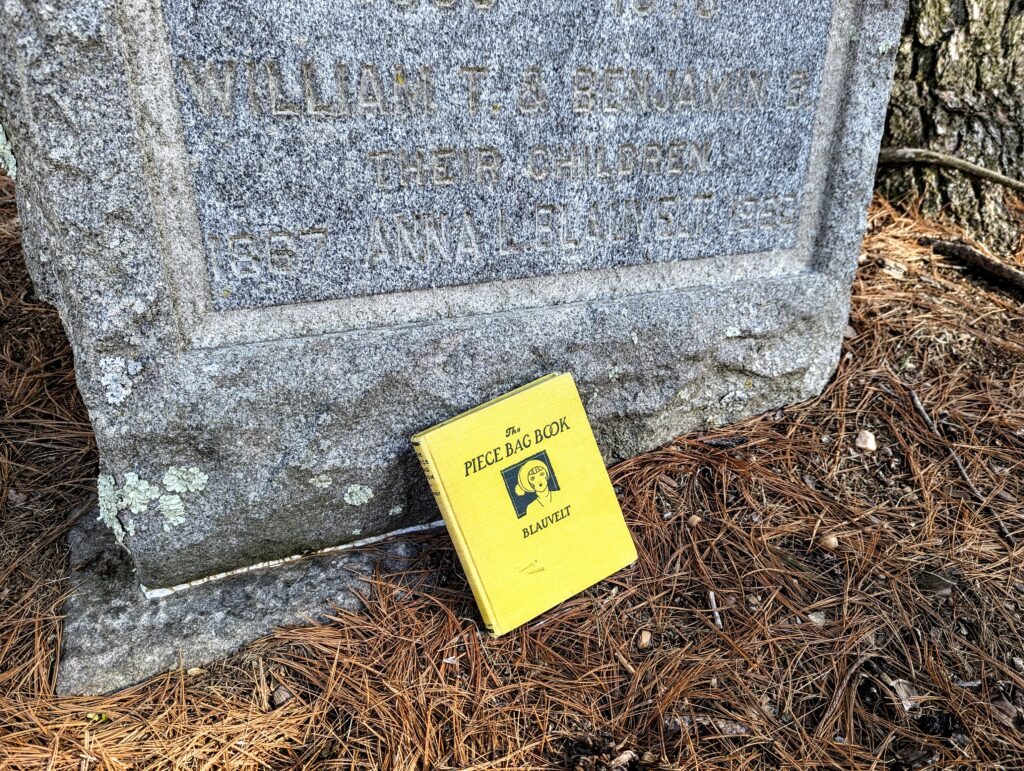

In Tivoli: The Making of a Community, Bernard B. Tieger gives a brief mention of the scandal that befell the Tivoli Baptist church, as reported in a New York City newspaper. It could well be that this passage was the only mention of John H. Boyes’ existence in the last century and a quarter since his passing. His middle name of Heathcote was passed down to one of his sons, and perhaps someone descended from him may have some idea that one of their great-grandfathers was from England, or was once a Baptist pastor, or a portrait artist. That he thrashed against the expectations of the churches that attempted to employ him. That he didn’t fit their mold. Maybe he wanted more from everyone and everything.

Maybe he just wanted to make art and live a comfortable life. I don’t think he can be blamed for wanting such a thing. In order to pursue our passions, we must often submit to jobs we abhor and dearly wish we could use the time we spend attempting to keep our bills paid making art, or whatever it is that properly floats our boats.

However, Einstein is often (though perhaps mistakenly) attributed with saying “insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.” No one can say if Boyes was out of his mind or not, but the fact that he thought he could cause a scene to turn public opinion such that his employers would continue to pay him for work he did not perform after the termination of his contract, and to attempt to do so twice, is, shall we say, bonkers.

Legacy

As mentioned above, John Boyes and Lucinda Staples had eight children, only four of which survived to adulthood. Of the four who did not, only Olive I. Boyes (February, 1888 Himrod, Yates Co., NY–August 14th, 1888 Middletown, Monmouth Co., NJ) could be located as of this writing. She likely died of scarlet fever, aged only six months. Below are short biographies of the four surviving Boyes children.

Violet Lavinia Boyes (never married) 23 Apr 1884–2 Dec 1954

Born April 23rd, 1884 in Williamson, Wayne Co., NY when her father was a pastor there, Violet married stockbroker Walter Heinman on October 20th, 1906 in Manhattan. They lived together in the Bronx in 1910 with her brothers and sister. It’s not clear when she and Walter divorced, but in 1915 Violet was calling herself “Boyes” again, and living on Edgecombe Avenue with her siblings only a few miles to the west of the home she’d shared with Heinman. In 1925 Violet worked as a clerk at an insurance agency and lived with her brother Benjamin in the Bronx.

Violet and her sister Martha’s family would visit each other frequently, even as they got older, as seen in numerous social columns in Martha’s local paper. Violet Boyes died in Manhattan on December 2nd, 1954 and her name was recorded as Violet Heinman on her death certificate.

Martha Grace Boyes (Mrs. Frederick J. Russell) 7 Sep 1885–24 Apr 1972

Martha was recorded as “Grace” in the census when she was young, but appears to have gone by “Martha” for most of her life. As with sister Violet, she was born in Williamson, Wayne Co., NY on September 7th, 1885., She worked in a millinery in 1910 in the Bronx when she lived with her siblings a few years before she married Englishman Frederick J. Russell on April 8th, 1916 in Manhattan. Fred worked for a nearby power company. They appear to have had only one child, their son Howard Russell, born c.1924.

Martha died April 24th, 1972 at 86 in a nursing home in Brunswick, NJ. She had previously been residing with her son Howard Russell in Spotswood, NJ. She had lived in Waldwick, NJ for many years and was a member of Ramsey Baptist Church. Burial was to be in the George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus.

Benjamin Heathcote Boyes 25 Feb 1887–9 Apr 1968

Benjamin worked as a plumber in 1910 and in 1915 when he lived on Edgecombe Avenue in the Bronx with his siblings. His WWI draft card gives us a record of his middle name, which bolsters an unsourced claim that he shared it with his father. This record also says that he was born in Tivoli, but his father was working in Himrod in February of 1887 and they wouldn’t move to Tivoli for another two years. When he was drafted for WWI, Benjamin was working as a plumber at the Remington gun factory in Bridgeport Fairfield Co., CT. He served with the Military Police in WWI from September 29th, 1917 to July 19th, 1919, attaining the rank of corporal.,

When he came home, he lived with family at 170th Street in NYC. In 1925 he lived with sister Violet, and worked in an “exporting house”. His WWII draft card noted that Benjamin had blue eyes and blond hair, and stood 5’11” tall.

Later in life, he lived in Schenectady as seen in the 1950 census where he lived with other male lodgers about his age and worked for the US Army as an office clerk. Benjamin never married. His last residence when he died April 9th, 1968 was 33 Bergen Ave, Waldwick NJ, and he’s buried at George Washington Memorial Park in Paramus, NJ, presumably with his sister Martha and her family. Though it is not listed on the Find-a-Grave website as of this writing, his resting place is supposed to be marked with a flat bronze military veteran marker that his nephew Howard Russell got for him.

John Staples Boyes 25 Aug 1889–23 Jul 1968

John was a bank clerk in 1910 when he lived with his siblings in the Bronx.. He was born in Tivoli, stood 5’10” tall, and had blue eyes and brown hair.

By 1915 he was enumerated as a broker when he and his siblings lived on Edgecombe Avenue, and declared he was a cashier on his WWI draft card, working for stockbrokers Fanning & Buck Co.

John enlisted February 21st, 1918 in the New York Guard but was discharged May 29th; presumably he never served, having only been in the system for a few months.

He was a director for stockbrokers Freedman & Co. Inc. in Flushing when it was chartered in 1919 but in the 1920 census they called him a “cashier” at a brokerage. At that time he lived in Queens with his wife Catherine Robertson and their 10 month old first born son, John.. John and Catherine were married May 28th, 1918, one day before he was discharged from military conscription. They had two sons, John Robertson Boyes March 21st, 1919–June 6th, 2001, and Robert Heathcote Boyes December 3rd, 1924–December 12th, 2000. John R. Boyes married Lenore Ashton in 1943 and Robert H. Boyes married Yolanda M. DiGioia (the former Mrs. Alfred Sanetti).

In 1925 John’s occupation label was “broker” and newborn son Robert was added to the family. With a man named Max Goodney, John formed a brokerage called Goodney & Boyes at 11 Broadway in Manhattan as announced in the New York Evening Post of March 22nd, 1929—not a great year to be in stocks and bonds, which might explain what can be learned of his life after that year.

In 1940, John lived on Vermilyea Avenue in Manhattan, and, though he was marked as “married”, Catherine was out of the picture. His son Robert and sister Violet were with him (son John was off on his own already) and John’s new occupation was elevator operator. He would declare he worked for real estate firm Brown, Wheelock, Harris, & Stevens on East 75th Street in Manhattan on his 1942 WWII draft card, but perhaps all he did was run the lift. The family had this configuration in 1950 in Manhattan as well. John was a building super, and he and Violet were now both distinctly labeled as “divorced”.

It’s likely the siblings stayed in touch throughout their lives. In 1956 John and his brother Benjamin were driving around Saratoga, probably while John was visiting near Ben’s home in Argyle, Washington Co., NY, when, John claimed, a bee stung him causing him to lose control of the car. They went off the side of the road, but suffered only bumps and scrapes.

John died July 23rd, 1968 at Murray Hill in New York City at 78 years of age.

Sources below. If you would like to see the footnotes, download the pdf of this article HERE.

- 1900 Federal Census, Manhattan, New York Co., NY, John Boyes

- 1900 Federal Census, Manhattan, NY, 833 3rd Ave.

- 1900 Federal Census, Poughkeepsie, Dutchess Co NY, F.B. Van Dyne

- 1910 Federal Census, Bronx, NY, (dated April 18th), Trinity Avenue

- 1915 New York State Census, New York, NY, Edgecombe Ave, Benjamin Boyes

- 1920 Federal Census, Queens, NY, S 23rd St, John Boyes

- 1925 New York New York W 170th St #514, Benjamin H Boyes

- 1925 New York State Census, New York, NY, W 170th St #514, Benjamin H Boyes

- 1925 New York State Census, Queens, New York, 139th St., John Boyes

- 1930 Federal Census, Waldwick, Bergen Co NJ. Bergen Ave

- 1940 Federal Census, New York, NY, Vermilyea Avenue, John Boyes

- 1940 Federal Census, Waldwick, Bergen Co NJ Bergen Ave

- 1950 Federal Census, Schenectady, Schenectady. Co. NY

- Albany Argus, 5 May 1891

- Cert #55043 New York State, U.S., Death Index, 1957-1970

- Dundee Observer, 8 Feb, 1888

- Dundee Observer, Dundee, NY, 18 Apr 1888

- Dundee Observer, Dundee, NY, 2 May 1888

- Geneva Advertiser, Geneva, NY, 14 Sep 1886

- New Jersey, U.S., Death Index, 1848-1878, 1901-2017

- New Jersey, U.S., Deaths and Burials Index, 1798-1971 FHL Film Number 589314

- New York, New York, U.S., Death Index, 1949-1965 cert #24883

- New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Death Index, 1862-1948, cert #1823

- New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Death Index, 1862-1948, cert #22723

- New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937 cert #16498

- New York, New York, U.S., Extracted Marriage Index, 1866-1937 cert #26841

- New York, New York, U.S., Marriage License Indexes, 1907-2018 cert #9035

- New York, U.S., New York Guard Service Cards, 1906-1918, 1940-1948

- New York State, Birth Index, 1881-1942 cert #32010

- New York State, Birth Index, 1881-1942 cert #9453

- New York Tribune, 4 Sep 1919

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 7 Sep 1919

- Ontario, Canada Marriage Records

- Palmyra Democrat, Palmyra, NY, 21 Jul 1886

- Penn Yan Express, 19 Oct 1887

- Pine Plains Register, 1 Apr 1892

- Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 14 May 1891

- Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 18 Jun 1891

- Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 20 May 1891

- Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 3 Jun 1891

- Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 6 May 1891

- Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, 9 Oct 1891 “Fired From The Pulpit And Fired Out Of Court.”

- Poughkeepsie Evening Enterprise, 10 Apr 1894

- Poughkeepsie News-Press, 23 Feb 1892

- Poughkeepsie News Press, 4 May 1891

- Poughkeepsie News-Press/Columbia Republican, 8 Oct 1891

- Red Bank Register, Red Bank, NJ, 11 Jul 1888

- Red Bank Register, Red Bank, NJ, 20 Feb 1889 “THE PASTOR MUST GO”

- Red Bank Register, Red Bank, NJ, 24 Apr 1889 “THE PASTOR SHUT OUT”

- Red Bank Register, Red Bank, NJ, 25 Apr 1888

- Red Hook Journal, 15 Jan 1892, story from Poughkeepsie News-Press

- Red Hook Journal, 16 Oct 1891

- Rhinebeck Gazette, 23 May 1891

- Rhinebeck Gazette, 8 Mar 1892

- Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 21 Aug 1886

- Suffolk County News 2 May 1974

- The Central New Jersey Home News, 25 Apr 1972, Page 26

- The Marion Enterprise, Marion, NY, Jun 19, 1886

- The Saratogian, 27 Aug 1956

- U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939 #1918770

- U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1861-1985

- U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007

- U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014

- U.S., Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940

- U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918

- U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942